THE DANCE THEATRE of Harlem, the only ballet company in the nation that employs black dancers in any number, opens a week-long engagement on Tuesday at the Kennedy Center Opera House. But although DTH, as it is known, has drawn enthusiastic applause from critics over the years, the cheers cannot drown out the troubling question of why there are still so few blacks in other American ballet companies.

Why have so many skillful and popular black ballet dancers had to make their careers in Europe? And why, once established, have so few of these been able to return to starring positions at home?

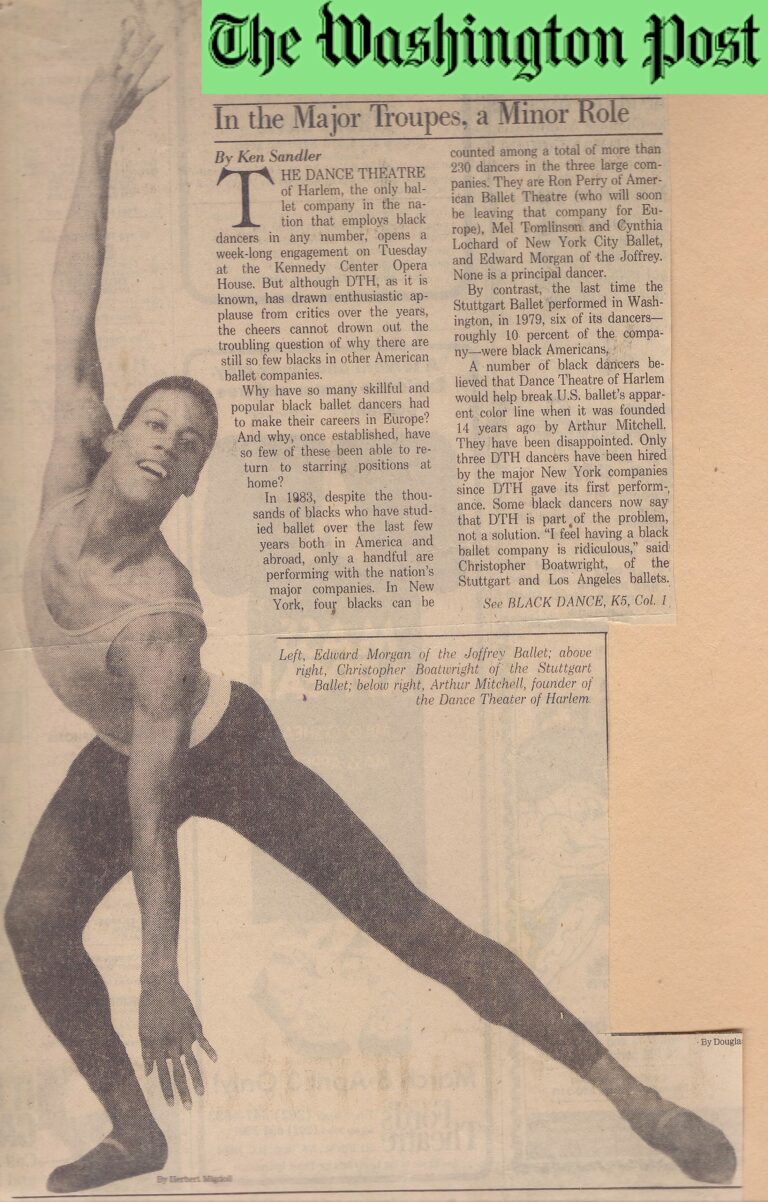

In 1983, despite the thousands of blacks who have studied ballet over the last few years both in America and abroad, only a handful are performing with the nation’s major companies. In New York, four blacks can be counted among a total of more than 230 dancers in the three large companies. They are Ron Perry of American Ballet Theatre (who will soon be leaving that company for Europe), Mel Tomlinson and Cynthia Lochard of New York City Ballet, and Eward Morgan of the Joffrey. None is a principal dancer.

By contrast, the last time the Stuttgart Ballet performed in Washington, in 1979, six of its dancers–roughly 10 percent of the company–were black Americans.

A number of black dancers believed that Dance Theatre of Harlem would help break U.S. ballet’s apparent color line when it was founded 14 years ago by Arthur Mitchell. They have been disappointed. Only three DTH dancers have been hired by the major New York companies since DTH gave its first performance. Some black dancers now say that DTH is part of the problem, not a solution. “I feel having a black ballet company is ridiculous,” said Christopher Boatwright, of the Stuttgart and Los Angeles ballets. “I’m not a black dancer. I’m a ballet dancer.”

Alvin Ailey first spoke out on the issue four years ago. Ailey, the black founder of the modern dance company that bears his name, said he warns blacks against planning careers in ballet because the white companies won’t hire them. Blacks, he said, “are never really looked at by American Ballet Theatre or New York City Ballet.

“We thought the panacea was going to be Dance Theatre of Harlem,” he continued. “I was under the impression that DTH was going to be the training ground for black dancers . . . but that didn’t quite happen.” EDWARD MORGAN, who performed here last week with the Joffrey Ballet, said he has never personally experienced outright discrimination. But he has heard stories. The small number of blacks performing ballet, he believes, is attributable to attitudes. And he thinks those attitudes are changing.

“There was a feeling,” he said, “that you needed a certain type of body, a certain kind of looks, to dance ballet. A long time ago, teachers would advise blacks who showed up for ballet class, ‘You should study more in the line of modern.’ And they would follow that direction, and they would lose out.”

That kind of misguided direction, he said, made itself felt upon the black community. “The feeling developed among blacks,” he said, “that ballet was not for them.”

Morgan’s own experience was free of that type of interference. He started with the Dallas Black Dance Theater, “and when my teacher saw I had some potential, she took me to another company, an all-white company, where I could get more classically trained.” From there, his progress was smooth. He was recently promoted from Joffrey II, the junior troupe, to the main company.

“One thing I do know,” he said emphatically, “is that blacks can dance ballet. And Arthur Mitchell has proved it.” THE TWO BLACK American ballet dancers best known in Europe are Christopher Boatwright and Paul Russell, formerly of the Scottish Ballet and now of the San Francisco Ballet.

Both Boatwright and Russell hold the rank of principal dancers and both have danced leading roles in major full-length ballets. Both accused the major ballet companies in New York of discrimination. And they said DTH has failed to prove itself a major training ground able to funnel blacks into the mainstream of ballet.

In contrast to these views are those of DTH founder Mitchell. He says he is not aware of any pattern of racial discrimination by major white companies. He also denies strongly that DTH was ever intended to create a pool of trained black dancers to be drawn on by the major companies.

He wants DTH to become one of the world’s great troupes on its own, and he wants the white companies to stay away from his crop of black dancers–something these establishment companies seem more than eager to do. (At the same time, Mitchell has hired a number of whites to dance with DTH.)

Mitchell, now 48, was the leading black ballet star performing in the nation years ago when he started DTH in 1969. He was then a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. He said he was so moved by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that he decided to devote the rest of his life to helping other blacks

In contrast to these views are those of DTH founder Mitchell. He says he is not aware of any pattern of racial discrimination by major white companies. He also denies strongly that DTH was ever intended to create a pool of trained black dancers to be drawn on by the major companies.

He wants DTH to become one of the world’s great troupes on its own, and he wants the white companies to stay away from his crop of black dancers–something these establishment companies seem more than eager to do. (At the same time, Mitchell has hired a number of whites to dance with DTH.)

Mitchell, now 48, was the leading black ballet star performing in the nation years ago when he started DTH in 1969. He was then a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. He said he was so moved by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that he decided to devote the rest of his life to helping other blacks.

The idea spread that Mitchell’s company was to be the tool for integrating the establishment ballet world. But Mitchell says that never was his intent. “I set out to disprove the theory that blacks couldn’t dance classical ballet, and I have.”

But DTH, he said, “is no longer a social service.

“Are we going to continue as a social endeavor or are we going to develop as an artistic endeavor?” he asked. “There’s a point where you have to make a choice. More impact will be made if I make DTH a great company that happens to be black.

“What I have to do now is develop the company towards universal artistic standards so that it becomes one of the major artistic entities of our time.” THERE IS STILL a way to go before that can be accomplished, says former DTH dancer Russell. The Texas-born Russell was already training as a classical dancer at a Connecticut ballet company when he joined DTH. Of his six years there, which ended in 1977, he says in retrospect: “I lost quite a lot. The emphasis just wasn’t placed right at DTH. I don’t know whether it was a problem in guidance or a problem in the administration, but I know the talent among the dancers was there. There were many people who could have accomplished anything that any white classical dancer could have.

“If you were trained solely at DTH you would be able to roll on the floor” in an ethnic dance idiom, Russell said, “but you might not necessarily be able to do a double tour air turn to the knee . . .”

Russell chose to leave DTH and go to Leningrad to learn more about ballet. He took private lessons at the Kirov Ballet School, and later joined the Scottish Ballet, dancing the lead male roles in “Swan Lake,” “The Nutcracker,” “La Sylphide,” “Napoli,” “Cinderella” and “Giselle”–all in the full-length versions. It is an accomplishment that no other black now dancing in the United States has matched.

Said DTH’s Mitchell, in reply: “Where would Paul Russell be today if there had not been a Dance Theatre of Harlem? He would not exist.”DTH was also one of the options considered by Christopher Boatwright, who has just returned to the U.S. after 10 years with the Stuttgart Ballet, one of Europe’s leading dance companies. Although he had tentatively accepted an offer to join DTH, he decided a black company was not the answer, and joined the Los Angeles Ballet instead.

“I left America 10 years ago, and I thought that maybe in four years or so it might change a bit. Now, I come back and I see the situation in New York is worse. Artistic directors are just standing there aand cutting off the flow of black dancers . . . If I hadn’t gone to Stuttgart, I wouldn’t want to see now what would have become of me.” MITCHELL INSISTS that DTH cannot and will not be the main source of black ballet dancers for the major companies.

“If somebody should come and steal my dancers . . . that’s not fair. I wouldn’t do it to the American Ballet Theatre or the Joffrey or to Balanchine (the New York City Ballet), so why should they come and do that to me?

“Why should Balanchine come in and take the dancers from DTH and then we’ll be left high and dry with no dancers? Then your article would be: ‘Are the white companies draining DTH of all of its best dancers?’

“It’s just ethically not correct or fair. You don’t go around stealing dancers from one company for another.”

But whether he intended it or not, Mitchell’s company raised hopes that black dancers would proliferate in the major white companies–hopes which have not materialized. The reasons why are not clear, and clarification has not been forthcoming from the companies in question.

Neither American Ballet Theatre nor New York City Ballet has commented on the issue of blacks in ballet since they first were criticized by Alvin Ailey four years ago. Their press spokesmen said they had no one willing to respond to discrimination charges.

Do Russell and Boatwright believe that there is racial discrimination by major American ballet companies? “Yes,” they both said.

Russell recalled that early in his career, he went to the New York City Ballet-affiliated school, the School of American Ballet, to seek admission.

“I talked to an administrator and she said to me that there would be no opening at the New York City Ballet. And I was so naive, I believed her. When people were talking to me I thought they were honest.

“But I guess I really have no bitterness in my heart because I forgive people for their shortcomings. I try to push this stuff out of my mind even when it’s so obvious that I’ve been denied something because I’m black.”